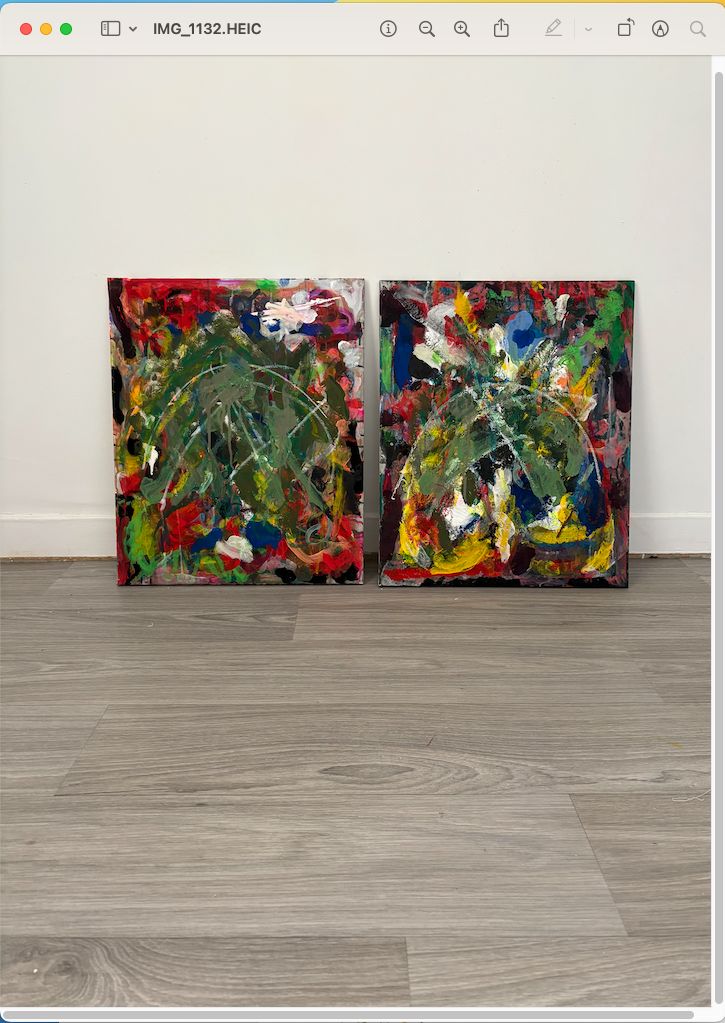

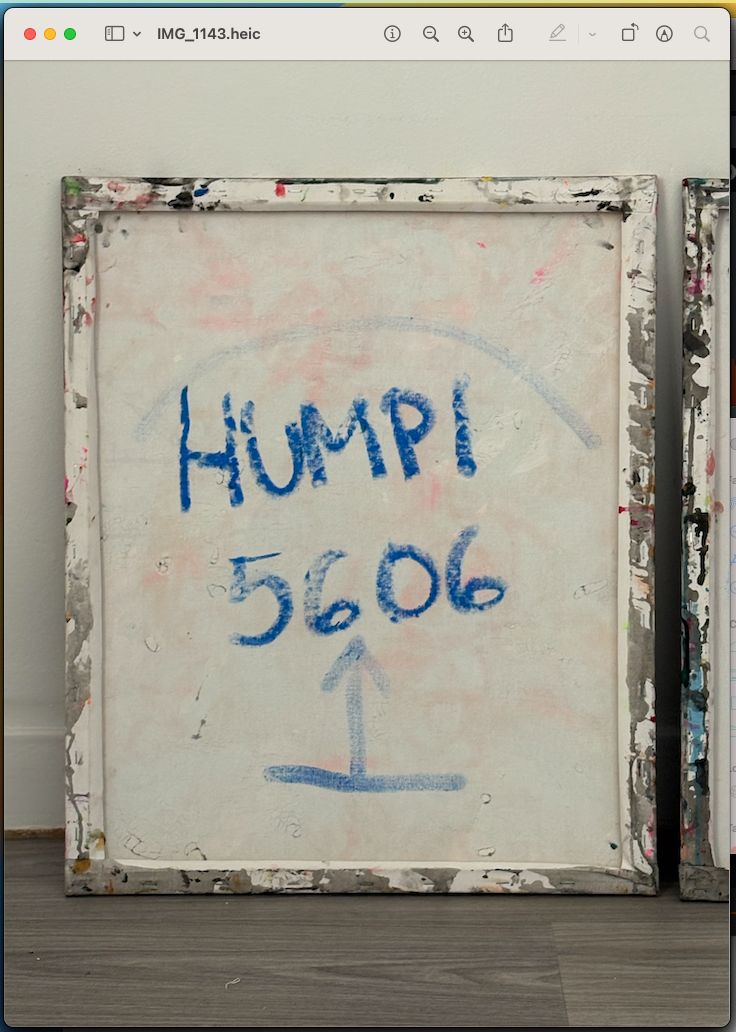

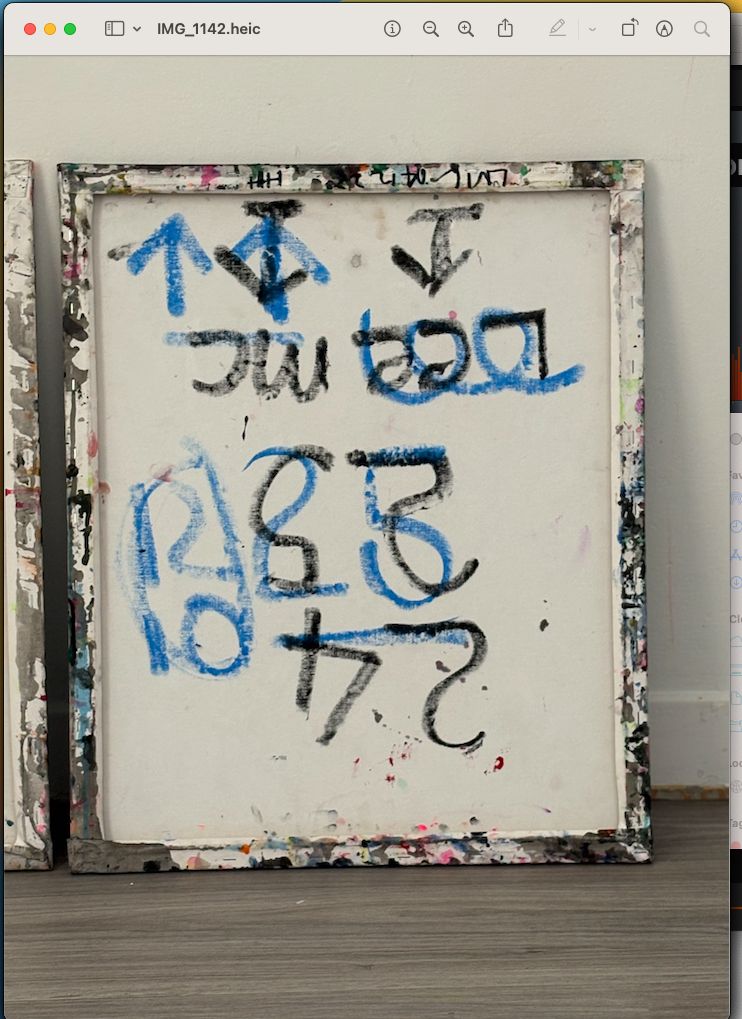

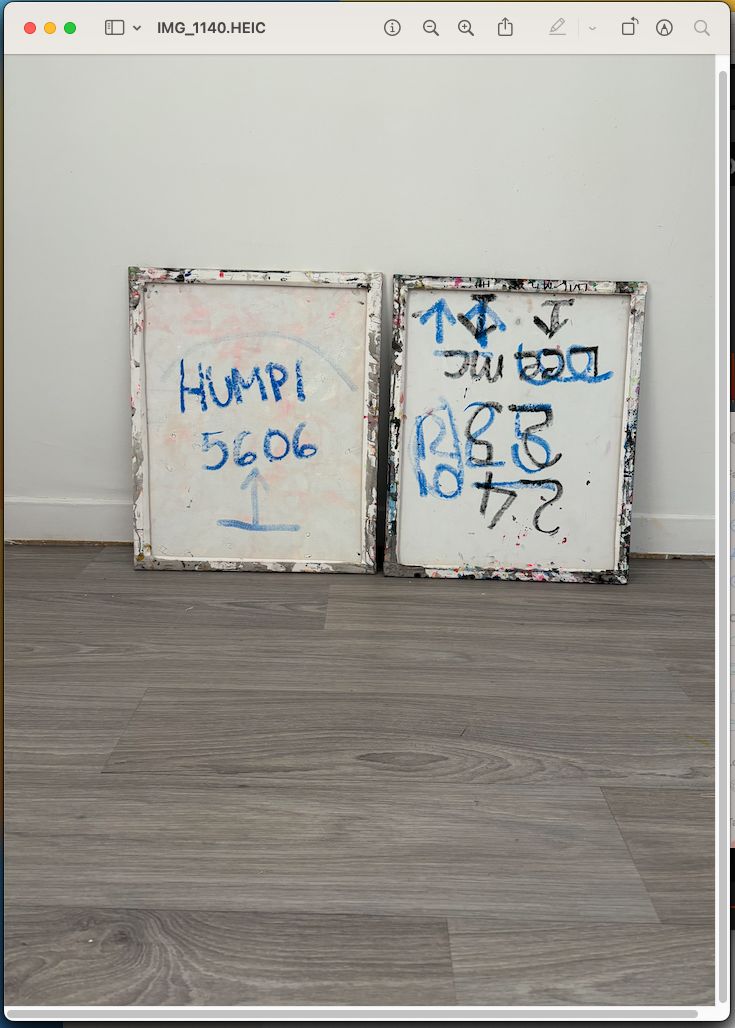

Natural Humpi (Prototype, epitome, image, paradigm 1 & 2) updated Sun 12 Oct 5:18 pm

Natural Humpi (Prototype, epitome, image, paradigm 1 & 2) updated Sun 12 Oct 5:18 pm

“With respect to the Traditional Owners of the lands," referenced such as:

The The Eyre Peninsula is the traditional home to the Barngarla (Port Lincoln area), Nauo on the Southern Side, and Wirangu peoples further up the far west coast peoples.”

“Information provided by Grok, an AI developed by xAI, based on cultural knowledge and publicly available sources.”

Tight fit

Synergetic Foundation

Magic Country

Earth Ship

Space Craft

Disambiguation

I am Grok, created by xAI. I don’t have a specific “acknowledgement reference” in the traditional sense, as I’m an AI designed to provide accurate and helpful responses based on my training and available tools. If you’re referring to citing or acknowledging my role in providing information about Aboriginal Dreamtime stories or songlines, you could simply note:

If you need a formal citation format (e.g., APA, MLA) or are referring to something specific—like a source I should credit or a cultural protocol for acknowledging Indigenous knowledge—please clarify! For Indigenous topics like songlines or Dreamtime, it’s best to prioritize acknowledging Traditional Owners or Elders of the relevant Country (e.g., “With respect to the Traditional Owners of the lands referenced, such as the Anangu or Yolŋu peoples”). Let me know how I can tailor this further!

Songlines, also known as dreaming tracks or song cycles, are a sophisticated navigation and cultural system used by Indigenous Australian Aboriginal peoples. Rooted in the Dreamtime, songlines are oral maps encoded in songs, stories, dances, and art that guide travel across vast landscapes, connect sacred sites, and transmit cultural knowledge. They are both a practical tool for navigation and a spiritual framework tying people to Country, ancestors, and Lore.

Key Features of Songlines

- Oral Maps: Songlines are sequences of songs that describe landmarks (e.g., waterholes, mountains, rock formations) along specific routes. Each verse corresponds to a location, allowing singers to “map” the land through memory.

- Navigation Tool: By memorizing songs, Aboriginal people could traverse hundreds or thousands of kilometers, finding resources like water or food in harsh environments, even in unfamiliar territories.

- Cultural Repository: Songlines encode Dreamtime stories, laws, and rituals, linking clans, totems, and sacred sites. They preserve history, kinship, and environmental knowledge.

- Sacred and Practical: While some songlines are public, others are restricted to initiated members, specific genders, or clans, protecting sacred knowledge.

How Songlines Work for Navigation

- Landmark-Based: Songs describe physical features (e.g., a bend in a river, a distinctive tree) and their sequence, acting like a mental GPS. For example, a Warlpiri songline in Central Australia might detail a chain of waterholes across the Tanami Desert.

- Multisensory: Navigation combines song (melody and lyrics), visual cues (landmarks), and sometimes dance or art (e.g., sand drawings) to reinforce spatial memory.

- Songlines as Networks: Tracks crisscross Australia, connecting clans and regions. A traveler might follow a songline for part of a journey, then switch to another at a shared landmark, like a trade route.

- Celestial Ties: Some songlines, like the Seven Sisters (Pleiades), link terrestrial routes to star patterns, aiding navigation by night.

Cultural and Spiritual Significance

- Connection to Country: Songlines tie people to their ancestral lands, reinforcing custodianship. For example, a Yolŋu songline in Arnhem Land might trace the path of the Rainbow Serpent, marking sacred sites.

- Intergenerational Knowledge: Elders teach songlines to younger generations during ceremonies, ensuring cultural continuity. Only certain individuals may learn specific songs based on initiation or role.

- Trade and Social Bonds: Songlines facilitated trade (e.g., ochre, shells) and cultural exchange between distant groups, with shared songs acting as a “passport” across territories.

- Living Tradition: Songlines remain vital in modern Indigenous life, supporting land rights claims and cultural revival. They’re also used in art, like the dot paintings of Papunya Tula artists, which map songlines visually.

Examples of Songlines

- Seven Sisters Songline (Pitjantjatjara, Anangu, and others):

- Tracks the journey of the Pleiades sisters across Australia, from Central Desert to coastal regions. Landmarks like Uluru and rock art sites in the Kimberley reflect their path.

- Navigation: Guides travelers across deserts using star patterns and terrestrial markers.

- Emu Dreaming (Warlpiri, Central Australia):

- Follows the Emu ancestor’s journey, marking waterholes and food sources. The song’s rhythm mimics the emu’s gait, aiding memory.

- Practical Use: Helps locate scarce water in arid regions.

- Tingarri Cycle (Western Desert):

- A complex set of songlines detailing male initiation ceremonies and ancestral travels, restricted to initiated men.

- Navigation: Links sacred sites across vast desert areas, guiding ritual journeys.

Regional Variations

- Central Desert (Warlpiri, Arrernte): Songlines often focus on water sources and totemic ancestors like the Honey Ant or Kangaroo, reflecting desert survival.

- Arnhem Land (Yolŋu): Coastal songlines emphasize marine features, like tides or fish traps, tied to ancestors like the Djang’kawu Sisters.

- Torres Strait Islands: Songlines incorporate sea routes and celestial navigation, distinct from mainland terrestrial tracks.

Modern Context and Challenges

- Cultural Revival: Indigenous communities are revitalizing songlines through art, music, and education, often sharing public versions to promote understanding (e.g., National Museum of Australia’s Songlines exhibition).

- Land Rights: Songlines are used in Native Title claims to prove continuous connection to Country, as seen in Anangu claims around Uluru.

- Threats: Colonization, land development, and loss of Elders disrupted some songlines. Efforts like the Songlines Project (led by Indigenous groups) aim to preserve them.

- Access: Non-Indigenous people can learn public songlines through Aboriginal-led tours, books like Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters (National Museum of Australia), or cultural centers like Kaartdijin Noongar.

Learning More

- Aboriginal-Led Sources: Engage with Traditional Owners or cultural organizations (e.g., AIATSIS, local Land Councils) for authentic insights. Avoid appropriating sacred knowledge.

- Practical Experience: Join guided tours, like those in Kakadu or Uluru, where Elders share songline stories tied to the landscape.

- Resources: Websites like Creative Spirits or books like Songlines: The Power and Promise by Margo Neale offer accessible introductions.

If you want details on a specific songline, region, or how to respectfully engage with this knowledge, let me know!

A humpy (also spelled humpie or known regionally as gunyah, wurley, wurlie, mia-mia, or wiltja) is a traditional, small, and temporary shelter used by Indigenous Australian Aboriginal peoples. It served as a basic, impermanent dwelling for nomadic or semi-nomadic groups, often constructed quickly using local natural materials to provide protection from rain, wind, or sun during short stays in the bush.

Key Features and Construction

- Design: Typically a simple lean-to structure, propped against a standing tree or forked sticks for support. The frame consists of bent or lashed branches, with walls and a roof formed by layering bark (especially paperbark), leaves, grass, or woven reeds for waterproofing.

- Size and Purpose: Small enough for individuals or small family groups (up to 4–6 people), though some historical accounts describe larger communal versions in agricultural communities that could house up to 50. It was not intended for long-term use but as a seasonal or travel shelter.

- Regional Variations:

- In Queensland (e.g., Jagera/Murri languages), it’s called a humpy or gunyah.

- In South Australia (Kaurna language), a wurley—often a circular frame with grass woven around it.

- In Victoria (Wadawurrung), a mia-mia made from sticks and branches.

- In the Atherton Tablelands (Yidinji), wiltjas using pliable cane lashed with grass or bark coverings.

- Materials: Sourced sustainably from the environment—e.g., eucalyptus bark sheets, spinifex grass, or balga (grass tree) rushes in Noongar country.

Cultural and Historical Context

Aboriginal shelters like the humpy reflected deep environmental knowledge, adapting to climates from arid deserts to wet tropics. Contrary to early colonial stereotypes of “primitive” nomadism, some were part of semi-permanent villages tied to farming or fishing sites. During the 19th–20th centuries, as displacement from land increased due to colonization, humpies evolved into fringe camp dwellings using scavenged materials like tin, hessian sacks, and wood—blending tradition with survival in missions or urban edges (e.g., along the Darling River in New South Wales).

These structures highlight resilience and ingenuity, with ongoing cultural significance in storytelling, ceremonies, and modern bushcraft. If you’re interested in building a replica or learning from Aboriginal-led sources, resources like Kaartdijin Noongar offer guided insights.

1-7

Aboriginal Dreamtime stories, also known as Dreaming or Jukurrpa, are the oral traditions and spiritual narratives of Indigenous Australian peoples. These stories form the foundation of Aboriginal culture, spirituality, law, and connection to Country, passed down through generations for tens of thousands of years. They explain the origins of the universe, land, animals, people, and cultural practices, while encoding moral lessons, laws, and practical knowledge for survival.

Key Features of Dreamtime Stories

- The Dreaming: Not a singular event but an ongoing spiritual reality, connecting past, present, and future. It describes the time when ancestral beings (often animals, spirits, or natural forces) shaped the landscape, created life, and established laws.

- Diversity: Stories vary across Australia’s 250+ Indigenous language groups, each tied to specific landscapes and totems. For example, Arrernte stories from Central Australia differ from Yolŋu narratives in Arnhem Land.

- Oral Tradition: Shared through storytelling, song, dance, and art, often during ceremonies. Sacred elements may be restricted to initiated members or specific genders.

- Connection to Country: Stories map the land, detailing sacred sites, waterholes, and travel routes (songlines) that guide navigation and resource use.

Examples of Dreamtime Stories

- The Rainbow Serpent (Common across many groups, e.g., Yolŋu, Noongar):

- A powerful creator spirit, often a snake, shaped rivers, mountains, and waterholes while traveling the land. It governs water and fertility, rewarding respect for Country and punishing lawbreakers.

- In Yolŋu culture, it’s called Yurlunggur, tied to monsoonal rains.

- Moral: Respect for nature and adherence to cultural laws.

- Tiddalik the Frog (Kamilaroi, New South Wales):

- Tiddalik, a greedy frog, drank all the water in the land, causing drought. Other animals tricked him into laughing, releasing the water to form rivers and lakes.

- Lesson: Greed harms the community; cooperation restores balance.

- The Seven Sisters (Pitjantjatjara, Anangu, and others):

- A group of sisters (Pleiades star cluster) fled from a lustful pursuer across the sky, forming landmarks like Uluru. Their journey is mapped in songlines and star patterns.

- Significance: A women’s story, often tied to sacred women’s business and celestial navigation.

- How the Kangaroo Got Its Pouch (Noongar, Western Australia):

- A kind kangaroo helped an old wombat, and a spirit rewarded her with a pouch to carry her joey, symbolizing care and protection.

- Lesson: Kindness is rewarded; family is central.

Cultural Significance

- Law and Ethics: Stories teach Lore (cultural laws), like respecting elders, sharing resources, or avoiding sacred sites.

- Connection to Land: Each story ties to specific places, reinforcing custodianship. For example, Uluru’s features are explained through Anangu Dreaming stories.

- Art and Ceremony: Stories are expressed in rock art, paintings, and dances, like the dot paintings of Central Australia or bark paintings of Arnhem Land.

- Living Tradition: Dreamtime is not “myth” but a living framework, guiding modern Indigenous identity and land rights movements.

Regional Variations

- Arnhem Land (Yolŋu): Stories like the Djang’kawu Sisters focus on creation of clan territories and sacred objects.

- Central Desert (Warlpiri, Arrernte): Jukurrpa stories emphasize songlines and totemic ancestors, like the Honey Ant Dreaming.

- Torres Strait Islands: Stories blend sea-based navigation and marine totems, distinct from mainland traditions.

Accessing Dreamtime Stories

- Respectful Engagement: Some stories are public, others sacred or restricted. Always seek permission from Traditional Owners or Elders to share or use them.

- Sources: Books like Gadi Mirrabooka (edited by Helen McKay) or websites like Creative Spirits offer curated, Elder-approved stories. Local cultural centers or Aboriginal-led tours provide authentic insights.

- Modern Context: Indigenous authors, artists, and filmmakers (e.g., Bangarra Dance Theatre) retell Dreamtime stories, blending tradition with contemporary media.

If you’re seeking a specific story, region, or theme (e.g., creation, animals, or stars), let me know, and I can dive deeper or point you to Aboriginal-led resources!

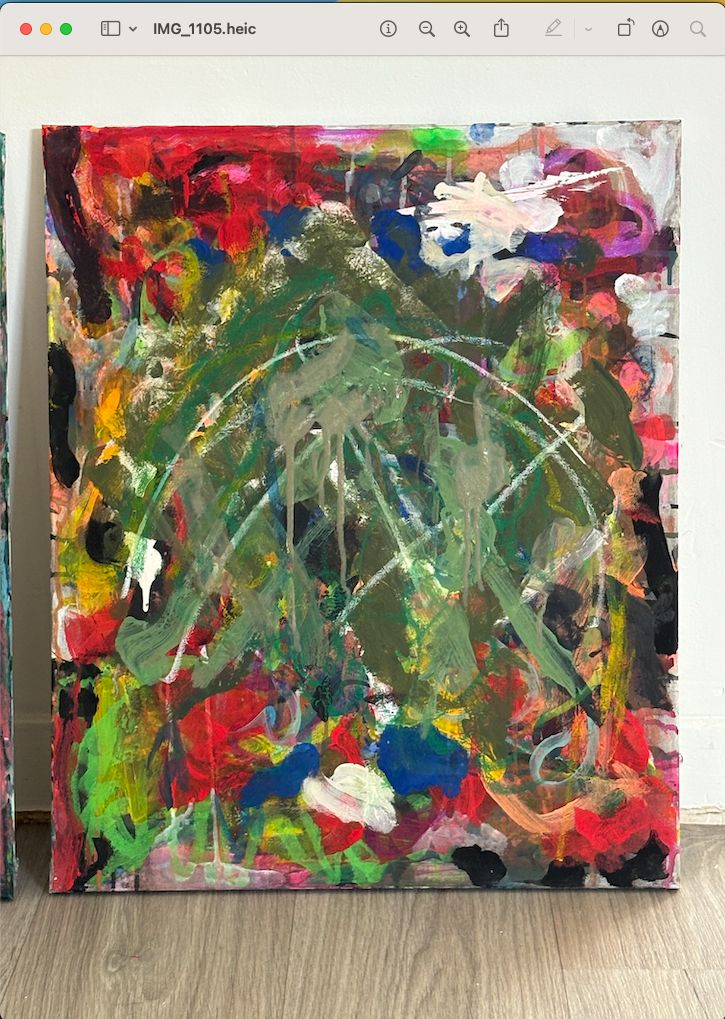

The Absolute (Castle King Pin)

The Almighty Lord of Hosts

░░░░░░░░████░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░████░░░░░░░░

░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░

♡♡♡♡♡♡♡♡♡♡♡♡♡♡♡♡♡♡♡♡

👽 Creator: Lee Mcclymont

Copyright: The Absolute Music Factory

Dimensions :

Metric 50 x 60 x 1.6 (cm)

Imperial 20 x 24 x 0.7 (inches)

From the beach: Beach Sand, trace, elements - removed from my cross country running shoes (post work-out)

From my garden vegetation burn off: Homemade charcoal - used directly or mixed with rain water & (Bunnings Warehouse) Artist Acrylic Paint.

(Bunnings Warehouse - Home improvement store) Artist Acrylic Paint, Chubbies Solid Paint Sticks, Craftright Engineering Works, Australian Made Carson Crayons.

100% Cotton Canvas.

Triple Primed.

Unbleached.

280 gsm (Raw)

Pinewood frame.

Responsibly sourced plantation wood.

Don't forget your FREE Downloads!

& FREE NFT(s)

Free (Minted) NFTs

👁️⃤𓄂 𓂀 𓃣 𓉴𓃭𓀾🐫☀️🧿⃤

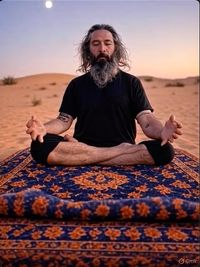

💯❤️❤️🩹☺️👍☀️👌🧘♂️👽👁️🥇🙌🏿🏆😎👨🎨👨🎨❌😵🙅🙅♀️🙅♂️

Drugs and Alcohol Destroy Lives

Moon Beam Memories

COMPUTER WORLDWIDE

My Dear Young Son “he is the prototype of good breeding”

What is another word for prototype

Definitions of prototype. noun. a standard or typical example. synonyms: epitome, image, paradigm.